Proclaimed, Therefore Protected?

Reflections from the Bush on Conservation, Governance, and Limits

This is a personal reflection written out of long-term interest in conservation systems and governance. It does not refer to any specific reserve, organisation, or individual.

Long before conservation became a policy objective, it was shaped by individuals who had witnessed the consequences of loss firsthand. Early pioneers and visionaries, including figures such as Paul Kruger, supported the proclamation of reserves as a means of restraint — a way to set land aside, impose limits, and protect it from short-term exploitation. Proclamation was never intended to replace stewardship or responsibility, but to reinforce them.

Many later reserves were founded in this same spirit, often through collaboration between private landowners and communities. Their success depended not on status alone, but on shared values, clear rules, and a commitment to long-term stewardship.

In times of uncertainty, it is tempting to believe that stronger laws, better financial controls, or official proclamation will solve complex conservation challenges. In conservation spaces, these steps are often presented as clear signs of progress — proof that protection has finally been secured.

Yet time spent close to the land, and watching systems unfold, suggests a more uncomfortable truth.

Protected areas are not saved by status alone.

They are saved by people, rules, and the consistent adherence to those rules.

Nature has an extraordinary ability to regulate itself when given space, limits, and time. Ecosystems recover, adapt, and correct imbalance. Human systems, however, often struggle to do the same. We are easily distracted by visible “wins” — improved income streams, tighter financial controls, expanded access — while deeper foundations quietly weaken.

Many reserves and parks were originally established by people who understood this difference. Their thinking was long-term. Stewardship mattered more than convenience. Rules were not optional — they were the framework that made protection possible.

Over time, however, priorities shift.

As conservation areas mature, financial stability and income streams understandably gain attention. Improved financial management, new revenue sources, and operational efficiencies are often celebrated as success — and in isolation, they can be positive. The danger arises when these “good deeds” begin to mask erosion elsewhere.

Financial improvement can never compensate for weakened adherence to rules.

When income improves, there is a subtle temptation to relax constitutional discipline and enforcement — particularly when doing so preserves social harmony. In many reserves, landowners, managers, and decision-makers are neighbours, friends, and social companions. Today they share a meal or a drink together; tomorrow one party is expected to enforce uncomfortable rules against the other.

This creates a quiet but powerful conflict.

Rules become harder to enforce when enforcement threatens relationships. Consistency gives way to discretion. Accountability softens under familiarity. Over time, governance shifts from being rule-based to relationship-based — and conservation pays the price.

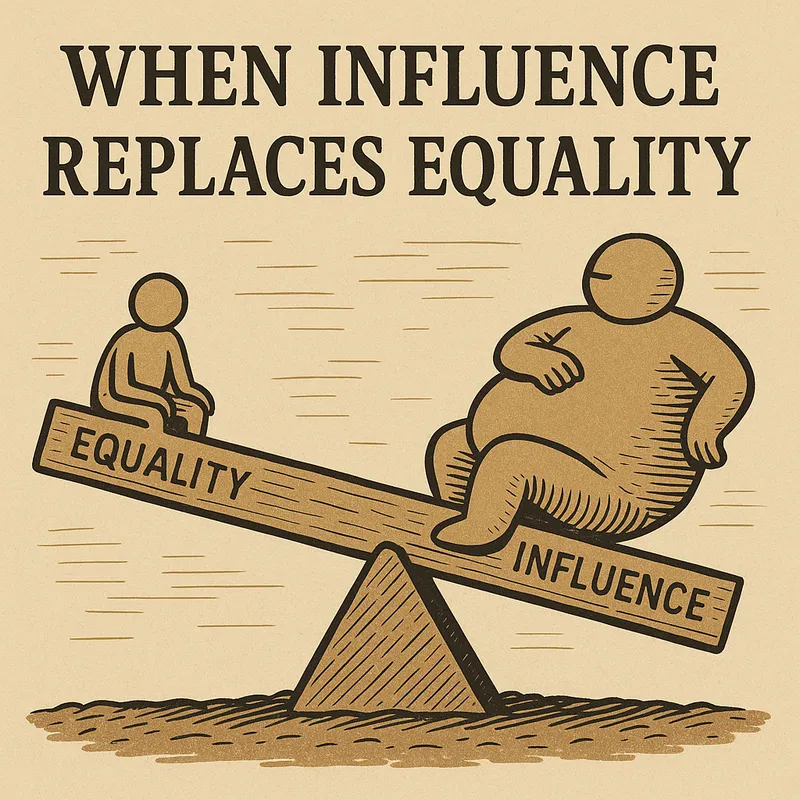

When influence replaces equality

This challenge deepens when influence within a reserve is uneven.

In shared conservation spaces, not all landowners carry the same weight. When a single large landowner — or a small group — holds greater financial resources, social reach, or informal authority, the balance of governance quietly shifts. Influence no longer flows mainly through agreed rules and processes, but through relationships, hospitality, and access.

Decisions may still appear democratic on paper, yet they are often shaped long before formal meetings take place. Nothing unlawful needs to occur. Influence works through familiarity, gratitude, and social comfort.

People are naturally reluctant to challenge those they socialise with or feel indebted to. Enforcement becomes awkward. Objections feel personal. Silence becomes easier than discomfort.

In such environments, rules are not openly broken — they are softened.

Processes are followed — but selectively.

Consensus appears genuine — but is often pre-shaped.

Rules exist precisely to protect shared landscapes from power imbalance — not to bend around it.

Paper protection and quiet erosion

Environmental tools suffer the same fate. Environmental Impact Assessments, management plans, and operational rules were designed to protect ecosystems from short-term pressure. On paper, they remain intact. In practice, their application is shaped by convenience, cost, and social tolerance.

Impacts are assessed narrowly rather than cumulatively.

Degradation is reframed as seasonal or insignificant.

Alternatives are dismissed as impractical or too expensive.

The paperwork is complete. The environment absorbs the cost.

The same erosion appears in enforcement. Ethical professionals invest time, training, and money to meet legal and safety standards. When others are allowed to bypass these standards without consequence — because enforcement would be unpopular or socially uncomfortable — integrity becomes a disadvantage. Standards decline not through rebellion, but through tolerance.

A lesson beyond conservation

This pattern is not unique to reserves.

Recent scares around major infrastructure — dam walls, power stations, water systems — reveal the same underlying problem. These structures do not fail overnight. They deteriorate slowly, visibly, and predictably. With modern technology, warning signs can be measured and flagged years in advance.

When failure appears to arrive “unexpectedly,” it usually means the signs were seen but not acted on.

Maintenance was deferred.

Responsibility was fragmented.

Costs were postponed.

Risk was managed on paper rather than addressed in reality.

The collapse of major infrastructure has followed this exact path — not a lack of laws or expertise, but a gradual erosion of discipline, accountability, and early intervention.

This matters deeply for conservation.

If we struggle to maintain concrete and steel — systems that are engineered and measurable — it is unrealistic to believe that complex living ecosystems will be protected by legal status alone.

A lesson from our flagship parks

For many years, South Africa’s flagship parks demonstrated what effective conservation could look like. Before COVID, Kruger National Park generated strong revenue, supported its own operations, and helped sustain the wider system. Infrastructure functioned, and institutional discipline still mattered.

COVID did not create today’s challenges — it exposed them.

As tourism revenue collapsed, maintenance was deferred, infrastructure deteriorated, and financial buffers disappeared. At the same time, long-standing failures outside park boundaries — such as sewage and water infrastructure breakdowns — continued to impact ecosystems flowing into protected areas. These problems were known long before COVID, yet persisted due to fragmented responsibility and weak enforcement across municipal, provincial, and national levels.

Kruger remains a globally important reserve. But its experience offers a sobering reminder: legal status, prestige, and revenue do not guarantee protection when governance weakens.

Why proclamation is not a cure

Proclamation is often presented as the ultimate safeguard. For government, it also serves another purpose: meeting national and international conservation targets. In this context, proclamation can become a tick-box exercise — a way to show progress on paper rather than to secure long-term ecological resilience.

Proclamation is not inherently wrong. But it is not a substitute for sound governance.

In systems where rules are already selectively applied, enforcement is uneven, social influence is strong, and financial pressure dominates decisions, proclamation risks amplifying existing weaknesses. It centralises authority without resolving underlying conflicts and can lock flawed assumptions into law.

Proclamation does not create ethical leadership.

It does not enforce rules.

It does not correct power imbalance.

It simply formalises whatever system already exists.

This is why hesitation is not opposition.

It is caution grounded in experience.

The false comfort of money and expansion

As communities struggle and institutions weaken, pressure grows to extract more value from protected land: expanding boundaries, adding roads, increasing access, raising fees and levies. While sometimes necessary, these are financial responses to systemic failure, not conservation strategies.

Money is not a cure for broken governance.

Expansion does not replace discipline.

Revenue cannot compensate for ignored rules.

In compromised systems, increased income often accelerates decline rather than preventing it — by deepening conflicts of interest and postponing difficult reform.

Back to basics — and a quiet hope

True conservation begins with fundamentals:

People with integrity and ecological understanding

Clear, well-designed rules

Consistent, impartial enforcement

Respect for ecological limits

Accountability, even when socially uncomfortable

Without these, no amount of proclamation, funding, or expansion will protect what we value.

There is, however, reason for hope.

Nature is resilient when pressure is reduced. Institutions can recover when rules regain meaning. Proclamation may yet have a role — but only once governance is strong enough to support it, not hide behind it.

Until then, caution is not resistance.

Restraint is not negativity.

And insisting on rules is not obstruction — it is stewardship.

Proclamation does not save a reserve.

People do. Rules do. and the courage to uphold them — especially when it costs something — does.

That is where real conservation begins — and where its future still lies.

So the question remains:

Are modern conservationists and landowners still guided by the vision and discipline of the pioneers — or have we mistaken activity, income, and status for true protection?

We can’t change the world today — but we can influence those who are willing to think.