When Neighbours Are Wild: The Giraffe Papillomavirus Story, Oxpeckers, and Coexistence in Dinokeng

Introduction

I’m now “retired” — or at least that’s what the paperwork says. In reality, retirement here simply means living inside the Dinokeng Game Reserve, where the daily timetable is set by whoever wanders past the lodge first. Sometimes it’s impala. Sometimes it’s a giraffe peering at us with that familiar expression of mild judgement.

My journey here started long before that, out in the veld, farming cattle and sheep. I later qualified as a Stock Inspector / Animal Health Technician, and eventually ended up behind a desk in the veterinary pharmaceutical industry — where the focus was almost always on domestic animals. Not because we loved cows more than kudu, but because that’s where the research money lived. And of course, domestic animals have one crucial advantage:

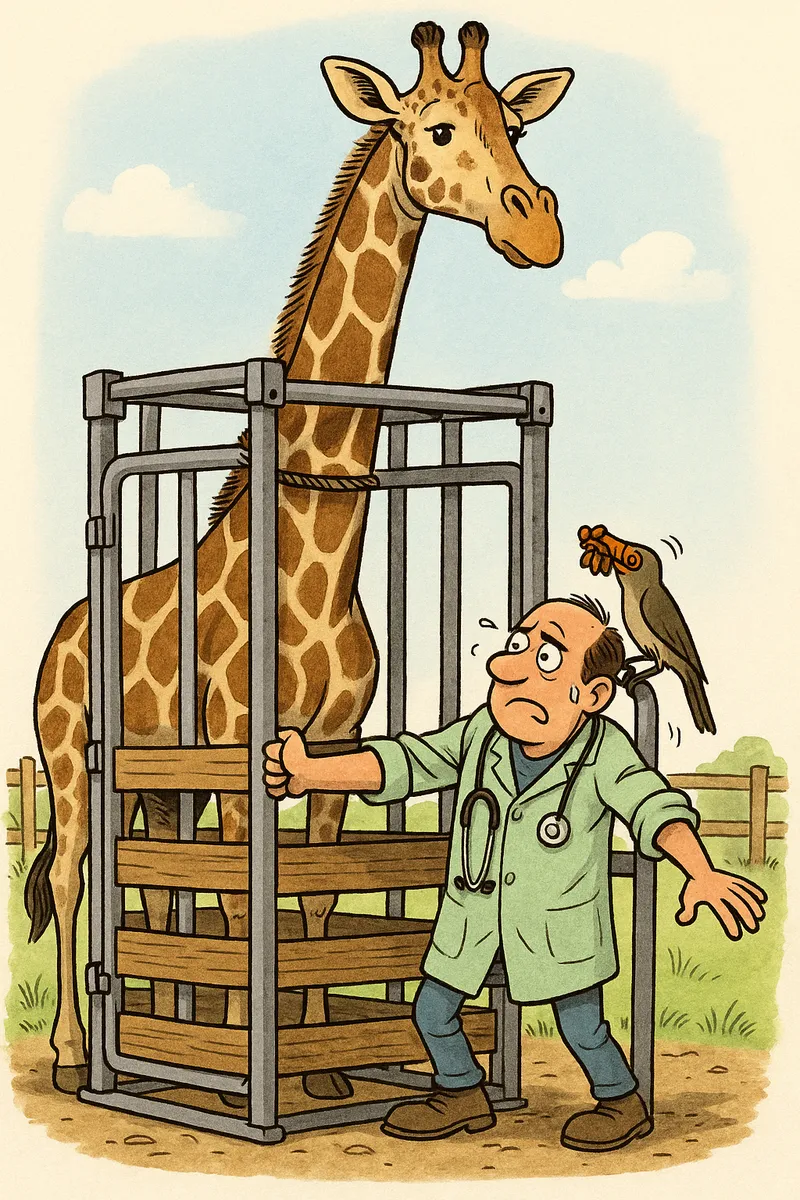

They fit into a crush pen and generally stand still while you look at them.

Giraffes are a little less cooperative than cattle. They’re basically a double-storey lodge on legs, with very firm opinions about anyone getting too close.

But whether you’re in a kraal, on a farm road, or under a Tree, one lesson never changes:

The bush speaks softly — but it always speaks.

My late father used to say:

“You have two eyes and two ears, and only one mouth — use them in that ratio.”

Look. Listen. Learn.

Lessons in the veld aren’t taught in classrooms.

A new limp.

A rough patch of hide.

An oxpecker behaving like it pays rent.

If you slow down, the bush tells you everything long before the textbooks do.

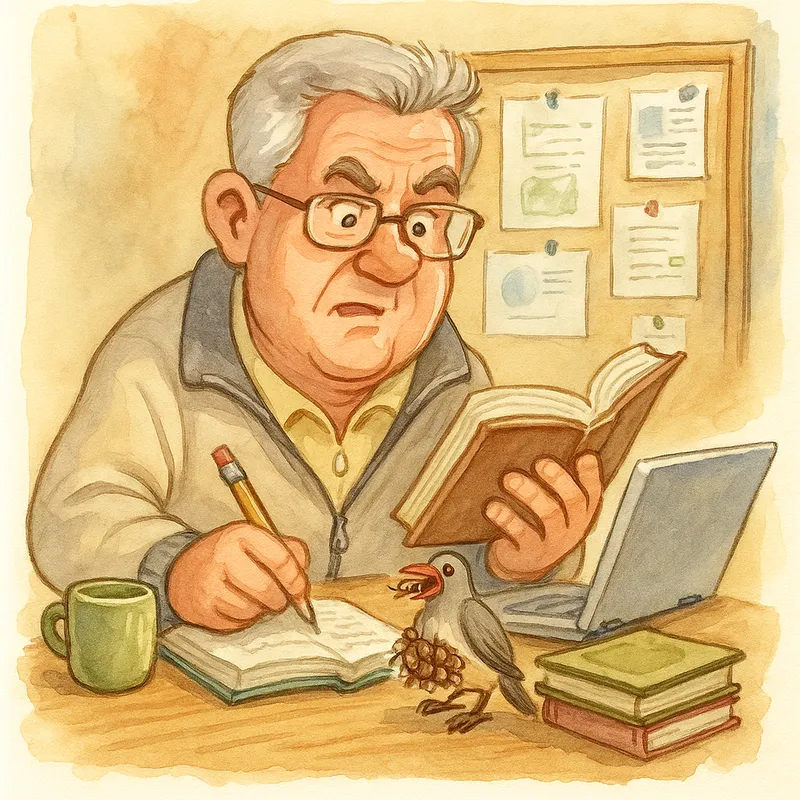

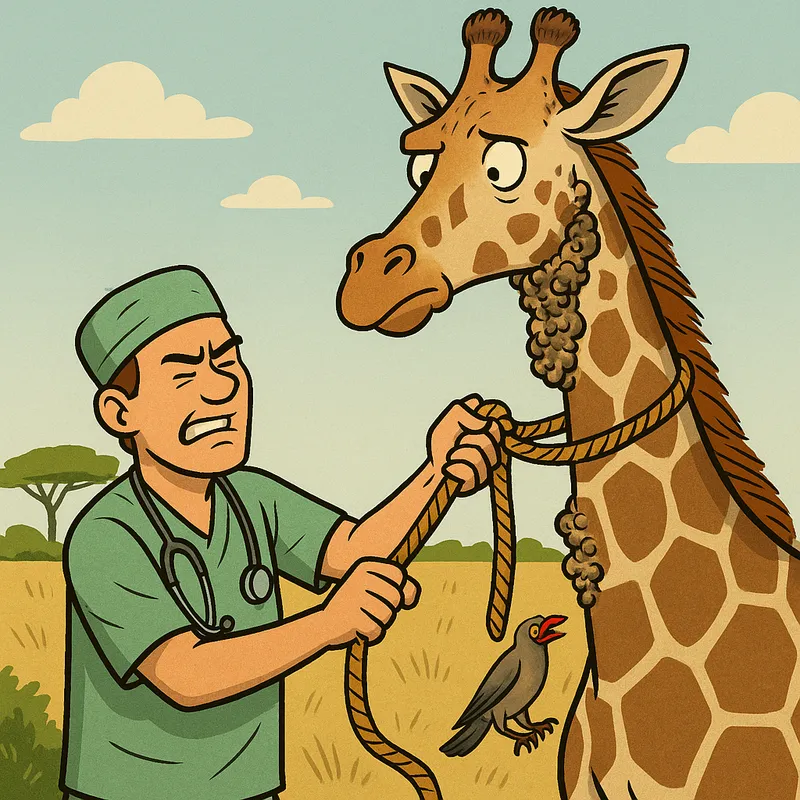

On a camping trip to Kruger, I noticed giraffes with rough, armour-like growths along their necks. Later, I saw the same here in Dinokeng. And that old instinct — the one that never really retires — whispered:

“Right. Pay attention.”

So began the research: veterinary papers, wildlife vets, scientists fluent in Latin before breakfast, and the inevitable late-night safari into the Google Serengeti.

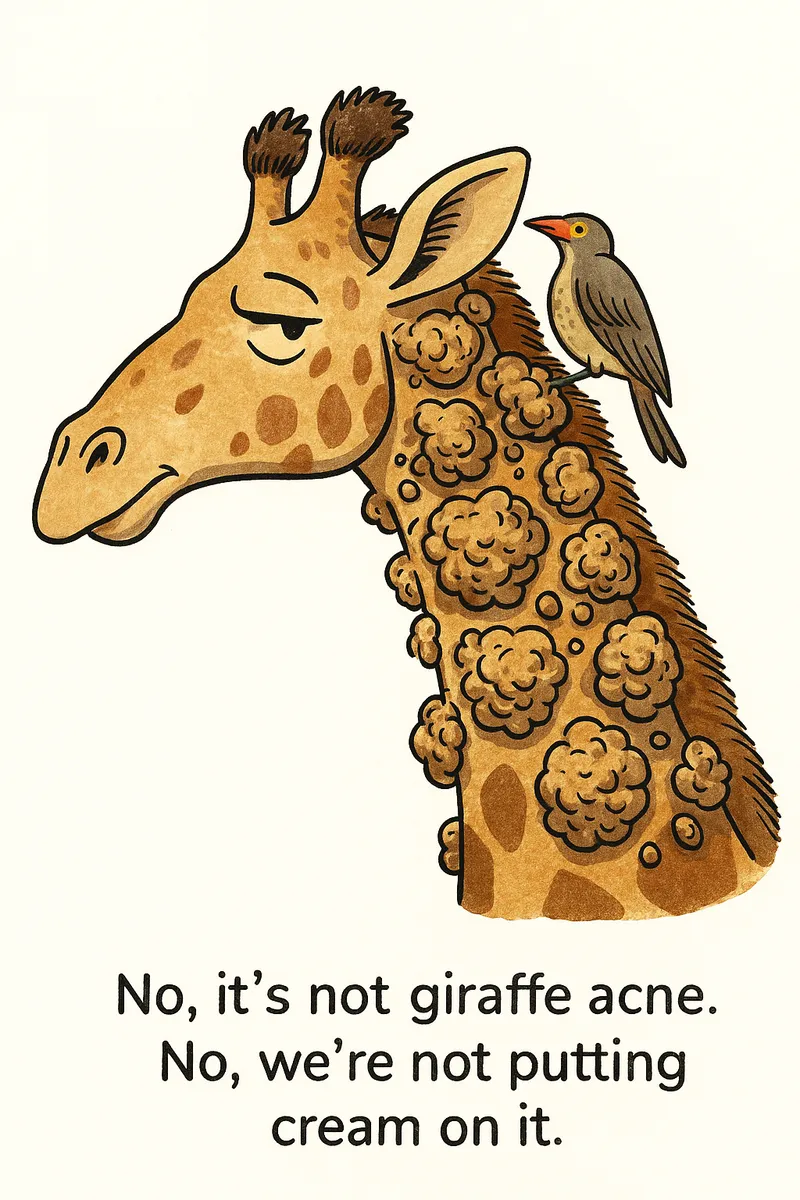

Soon enough, guests and guides began asking:

“Is it contagious?”

“Should we treat it?”

“Is the giraffe okay?”

And the classic:

“Should we put cream on it?”

So, for everyone who has pointed, wondered, whispered, Googled, or slowed the game drive — here’s what’s actually going on, and why nature is often already doing the healing.

When Africa’s Tallest Beauties Get Bumps

It first drew attention in Kruger, where rangers noticed giraffes with raised, lumpy growths along the neck and face. Not the usual thorn scratches or tick bumps — something that stayed.

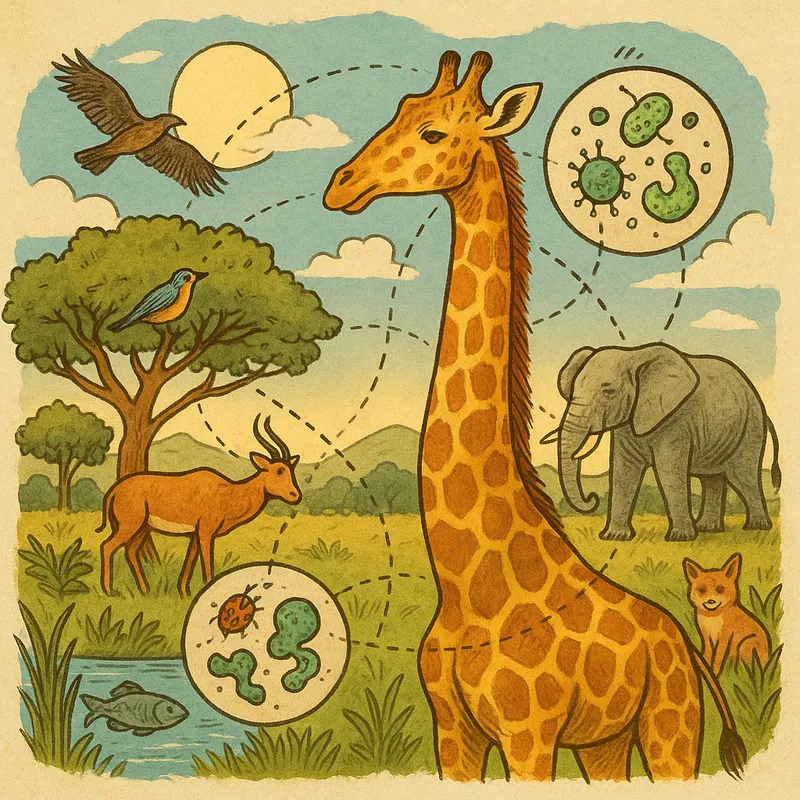

Lab work revealed the culprit: papillomavirus — the same family behind warts in cattle, horses, and even humans (nature really does enjoy running the same joke across species). Some strains even matched bovine versions, suggesting a past shared grazing encounter. Eventually, a giraffe-specific strain was confirmed:

Giraffa camelopardalis papillomavirus type 1 (GcPV1).

It causes fibropapillomas — those rough, knobbly patches that can make a giraffe look like it’s trying out medieval armour.

The reassuring part:

Most affected giraffes are healthy. They browse, walk, flirt, argue with oxpeckers, raise calves — life carries on. And in many cases, the bumps regress on their own once the immune system catches up.

So in Southern Africa, papillomatosis is generally:

Not fatal

Not rapidly spreading

Not a sign of giraffes evolving into dinosaurs

And not something requiring ointment, heroics, or ladders

In short: It’s mostly cosmetic, not a crisis.

Papillomatosis vs Giraffe Skin Disease (GSD)

This is where many guides, guests, and Google searches get tangled. There’s another condition seen mainly in Tanzania and Uganda called Giraffe Skin Disease (GSD). From a distance, it can look similar — rough, thick patches on the skin — but GSD is not caused by a virus.

Instead:

GSD is linked to tiny filarial worms living inside the skin.

These worms create thick, cracked, sometimes painful lesions, especially on the legs and joints. And this matters — because if a giraffe can’t walk well, it becomes an easier target for lions.

And nobody wants to be the giraffe at the wrong end of that equation.

Bushveld Summary

Condition | Caused By | Appearance | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

Papillomatosis | Virus | Small bumpy “armour patches” | Usually mild, often resolves naturally |

GSD | Worms | Thick, cracked, painful plaques | Can restrict movement & affect survival |

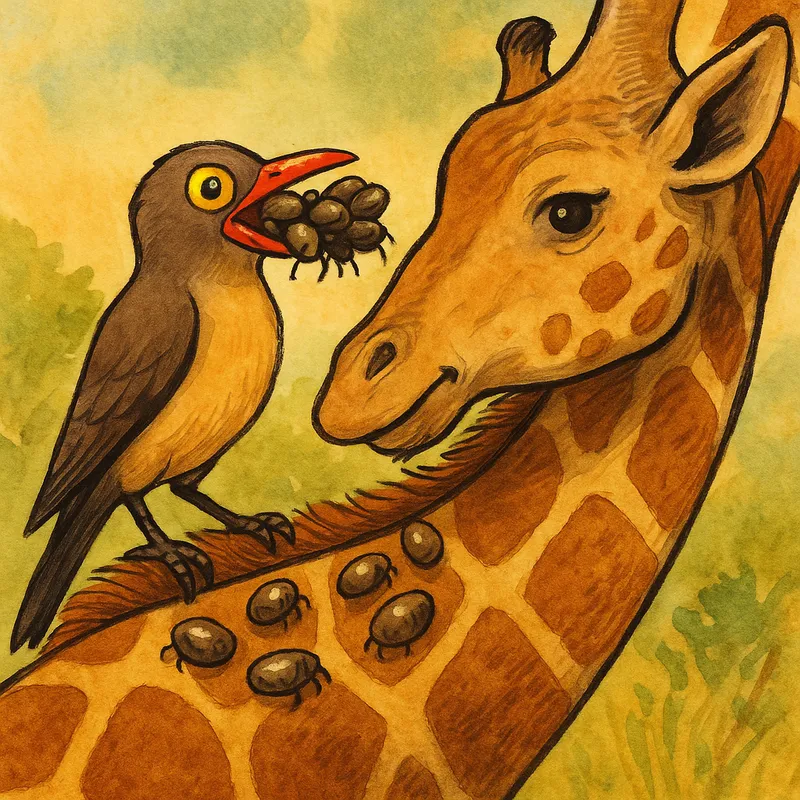

The Oxpecker Connection

Now, we need to talk about a certain bird.

The Red-billed Oxpecker — part dermatologist, part tick accountant, part agent of chaos.

Yes, they remove ticks and parasites.

But they also:

Pick at scabs (fresh is best)

Keep wounds open (buffet must stay open)

Enlarge lesions (repeat customers are good for business)

So if a giraffe already has papillomavirus or GSD, oxpeckers can unintentionally make it worse.

Not out of malice — just enthusiasm.

Think of them as:

Half doctor, half dentist, half chaos.

(Yes, that’s three halves. Oxpeckers don’t follow rules.)

The bush has a sense of humour.

And it is very dry.

When Worlds Meet: Domestic Animals & Wildlife

The bush may look wild and separate, but it isn’t sealed off. Farms, cattle posts, villages, lodges, and wildlife areas overlap, and when they do, so do the diseases.

Many wildlife illnesses didn’t start in wildlife. Some came from domestic animals, long before vaccines, fences, and permit offices existed.

Foot and Mouth Disease spreads faster than bush gossip — cattle can carry it, buffalo keep it going, and suddenly movement permits are ruining weekend braais.

Bovine TB likely jumped from cattle to buffalo, then to lions. And once lions have it?

Good luck explaining quarantine rules to someone who thinks you look like a snack.

Canine Distemper came from domestic dogs and has caused serious outbreaks in lions and wild dogs.

Try telling a lion to avoid the neighbour’s Jack Russell. I’ll wait.

And if COVID reminded us of anything, it’s that viruses don’t care about fences, boundaries, or management plans. They move where conditions allow.

And while giraffe papillomavirus doesn’t affect humans (no need to sanitize your binoculars), it does remind us:

In nature, everything is connected — sometimes beautifully, sometimes inconveniently — and the small, invisible things tell very big stories.

So what does this mean?

When wildlife and domestic animals share land, water, fences, ticks, flies, and the occasional overconfident oxpecker, they also share health risks.

In those overlaps:

Viruses don’t need passports

Parasites take the first ride available

Worms move house without notice

The bush becomes a two-way biological highway.

Sometimes the effects are small.

Sometimes they matter.

But they are always worth paying attention to.

Living together here means we’re all part of the same ecological conversation — whether we planned it or just arrived with a cooler box and binoculars.

And the bush’s quiet advice is always the same:

Watch early, understand early.

If not — expect surprises.

Back to Our Giraffes

Some giraffe papillomavirus strains match bovine ones — meaning, at some point, cattle and giraffes likely shared:

A grazing patch

A few persistent biting flies

Or one overly-enthusiastic oxpecker with no respect for boundaries

Nature doesn’t file things neatly.

Everything overlaps.

So those giraffe bumps aren’t “just a wildlife issue.” They remind us:

Wildlife, livestock, and people share one health story.

One landscape. One system. Many consequences.

Which is why paying attention isn’t just curiosity —

It’s conservation.

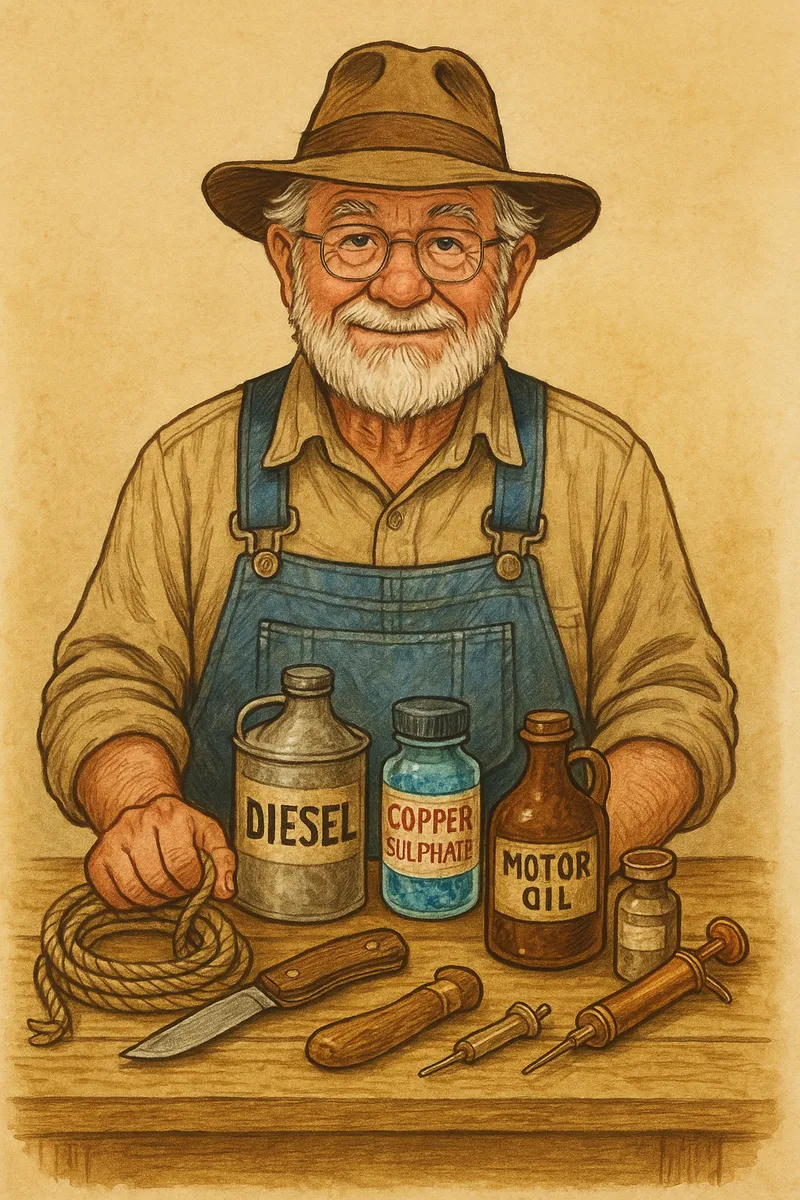

Old Farmers’ Wart Remedies — And Why They Don’t Translate to Giraffes

If you’ve spent time around cattle farmers, you’ll know every district has its wart cure. A few classics:

Tail hair tied around the wart

Cuts off blood supply. Wart drops. Simple. Effective. Very farm-laboratory-energy.Cut it to “wake up the immune system”

Scientifically valid — also a great way to introduce infection with a pocketknife that has lived many lives.The Rope Necklace Ritual

Tie a rope around the calf’s neck and wait.

Spoiler: it wasn’t the rope. The calf’s immune system just grew up.Diesel / Motor Oil

Please. No. Time did the healing. The diesel just made everyone smell like gearbox overhaul.Copper Sulphate Paste

Works… and burns anything else it touches.Autogenous Wart Vaccine

Surprisingly legitimate. Still used today.Feed the wart to the animal

Immune logic is there. Not essential.

All these are possible when your patient is a cow in a crush pen

Now imagine doing them on a giraffe:

Tying a hair around a wart (while avoiding being stepped on)

Standing under a giraffe with a rope

Rubbing diesel on a 5.5m wild animal

Trying to explain the insurance claim

This is where the bush gently says:

“No, my friend. Let nature handle this one.”

And, most of the time, it does.

The giraffe’s immune system sorts it out — no ladders, no creams, no diesel.

Sometimes the best treatment is:

Patience. Observation. And knowing when not to interfere.

From the Thorn Tree Lookout

Here at Thorn Tree, we sit where science, bush lore, and curiosity meet. Morning coffee often comes with giraffes passing by like quiet pieces of sky on legs. Out here, the stories are small, but they’re everywhere — written in hide, hoof, feather, and track.

So next time you see a giraffe with a few bumps, skip the ointment, the ladder, and your grandmother’s cattle remedies.

Just:

Look. Listen. Learn.

The bush teaches those who don’t interrupt it.

Even a wart can be part of a larger story — of immune systems, seasons, parasites, and one oxpecker with a very inflated sense of purpose.

Nature isn’t careless.

She simply works on her timeline, not ours.

If we pay attention, there is still much we don’t know — and that is normal. Wildlife health is an ongoing lesson, and we’re still listening, watching, and learning.

— Rodney du Toit

Thorn Tree Bush Camp — Where the wild calls, and curiosity never retires.

P.S.

The story isn’t finished — we’re still reading it, one giraffe at a time.

Thank you for walking this path with us. Keep an eye on this space for more bush moments, wildlife insights, and camping adventures from our side of the thorn trees. 🌿🦒🔥